This past year, I have indulged in reading Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe mysteries. The books were set in the time in which they were written and they span the 1930s through the early 1970s. As such they provide a glimpse of life in those times. Because Wolfe is running a business (and is a penny pincher) one also gets a lot of insight into the economics of the time. It is amusing to see people happy to get a quarter for a tip and to spend $4 on a 3 minute phone call from New York to Nebraska.

When the novels hit the post war era, the subject of income taxes comes up quite frequently and it is interesting to see how they effected behavior, albeit in a fictional setting. For instance, in Trouble in Triplicate, a prospective client thinks that his business associate (Mr. Blaney) is planning to kill him and he wants to hire Nero Wolfe to solve his murder if it occurs. He offers Wolfe $5,000 to do the job but Wolfe refuses. The client then asks:

"What's the matter, don't you want five thousand dollars?"

Wolfe said gruffly, "I wouldn't get five thousand dollars. This is October. As my nineteen forty-five income now stands, I'll keep about ten percent of any additional receipts after paying taxes. Out of five thousand, five hundred would be mine. If Mr. Blaney is as clever as you think he is, I wouldn't consider trying to uncover him for five hundred dollars."

Indeed, the marginal tax rate in 1945 was 90% for people making between $90k and $100k. At $100k it went up to 92% and maxed out at 94% at $200k. Of course, $90,000 in 1945 was worth over $1 million in 2013 dollars (according to the

Tax Foundations historical tables), so it was a high threshold. (Note: Someone making the equivalent of $440,000 in 2013 dollars, which is the 2013 threshold for the highest bracket, would have paid a marginal tax rate of 68% in 1945.)

This issue of taxes comes up repeatedly in the Nero Wolfe novels over the following decades. On several occasion people over to pay Wolfe in cash, with the implication that he might avoid reporting it on his incomes tax. Wolfe generally refuses to do so, though it is strongly implied that his assistant Archie Goodwin (who is the narrator of the stories) finesses the accounts to a large degree.

In the 1961 novel,

The Final Deduction (which refers to a logical deduction, not a tax one), Archie also uses his knowledge of Wolfe's proclivities and finances to talk him into helping a client retrieve a $500,000 ransom that has been paid for a one fifth share in whatever is recovered. Knowing that Wolfe will be reluctant to take on the case, Archie puts it to him this way:

"You might take a minute to look at it this way. It would be satisfactory to find something that ten thousand cops and FBI men will be looking for. And each year when you top the eighty-per-cent bracket you relax. I admit it's a big if, but if you raked this in and added it to what you already collected this year, you could relax until winter, and it's not May yet..."

In 1961, the 80% bracket for a single person (actually 81%) started at $70,000. Archie knows that Wolfe just earned a $60,000 fee, so this $100,000 would put him well over the top, even after deductions. If he earns it, than he can devote the rest of his year to tending his orchids, reading books and eating his gourmet meals. Wolfe's reaction to this is:

He closed his eyes, probably to contemplate the rosy possibility of months and months with no work to do and no would-be customers admitted. In a minute, he opened them and muttered, "Very well, bring him in."

The point here is that the "rosy possibility" of months without work is a very artificial one created by the tax structure. If Wolfe gets the $100k, in addition to the $60k mentioned and any other money he made in the year to date, he will probably be in the 89% tax bracket ($100,000 to $150,000) even after deductions for things like Archie's salary. Therefore, if someone offers him $10,000 to do a job, he will only get $1,100. As we saw above, Wolfe won't do much for that little. Of course, Wolfe might get his mind going for a net gain of $10,000, but a client would have to offer him a gross over $90,000 to do it. Even in Wolfe's world, that is an unusually high fee (which is part of why he is taking on the ransom money case in question).

The point here is that the high tax rate is creating a huge gap between what someone pays Wolfe to work and what he receives from doing so. Essentially, a client would have to be willing to pay nine times what Wolfe actually receives for doing a job. The "rosy possibility" of months of leisure is the result of the probability that no one would be willing to pay $9 for what Wolfe would be willing to do for $1.

While Wolfe might enjoy the enforced respite from work, this is a loss from a social point of view. After all, Wolfe would be sitting on his fat butt (literally both in terms of sitting and fat) for most of the year, turning away clients that would otherwise benefit from his services. Of course, there is a Keynesian upside to this situation in that, since Archie's salary is a business expense, Wolfe has little incentive to lay him off since doing so would decrease his deductions and probably push him into a higher tax bracket. But even then, the society would have Archie, supposedly the second best private detective in New York City, sitting on his butt too (though, admittedly a much smaller one).

Now, of course, Nero Wolfe is a fictional character and accepts this situation because he is written as being moderately scrupulous about his taxes and limited in his means of being creative with expenses. Were he less scrupulous, he might accept cash under the table but, more importantly, were he in a corporate setting, he might find other ways of getting paid that can't be taxed.

Indeed, in corporations during the days of 50+% tax brackets, non-monetary benefits were an important part of executive compensation. Things like company cars, executive dining rooms, memberships at clubs, and business trips with little business in them were part of the perks offered to higher paid executives. This was because just about anything that could be justified as a business expense to the IRS was an efficient way to compensate people in a high tax bracket.

For instance, a 1961 Cadillac sold for about $6,000. If it could be justified as a business expense it would cost the company about that much to offer it to an executive as part of the compensation package. If the company wanted to offer enough money to buy the car to an employee in the 81% tax bracket, it would have to pay over $54,000. The same logic (or illogic if you prefer) applies to everything else.

Fast forward to today when the top tax rate is 39.6%. A company could offer someone a car worth $40,000, but the cash value (factoring in taxes) to a highly paid executive would only be about $67,000. In some cases, this might work out to their mutual advantage (if current IRS rules would allow it), but it may be that the executive would rather just have the $40K ($24k after taxes) to do whatever he/she wants with it. In technical terms, the tax benefit may be offset by the deadweight loss associated with not being able to spend the money as the executive wants.

More importantly, the old system of providing perks to executives hid many of the costs of employing them not just from the IRS but also from stockholders. Therefore, it was doubly in the interests of management to hide non-monetary compensation in their business expenses and, ultimately, it was in the interest of stockholders to move their corporations away from it, especially after the top marginal tax rate dropped from 70% in 1981 to 50% in 1982-1986, to 38.9% in 1987, and to 28% in 1988.

Of course, IRS rules, and the stringency with which they are applied, are a big part of the story. However, the IRS is susceptible to political pressure and, though I can't say for certain, there was probably a lot of pressure applied by businesses to allow expenses to be more loosely interpreted when perks were so important to corporations.

The point here is that high tax rates can distort the incentives of individuals. At the simplest level they can enforce lethargy on people like Nero Wolfe or they can encourage tax avoiding behavior on people who refuse to sit on their butts. At a more complex level, they can encourage institutionalized patterns of behavior that are far from optimal. In all cases it threatens to lead to less efficient outcomes from a purely Neo-classical point of view.

That being said, I have to add that today's tax rates in the US are far less distorting than in the past. I have listed the top marginal tax rates from 1918-2013 below. You can see a marked difference in the top rates that prevailed from 1932-1981 and those that have been in place since 1987. It is also interesting to note that most of the Reagan years saw a 50% top rate that bridges the two eras.

Here are the top marginal tax rates from 1918-2013 (again from

taxfoundation.org)

1917-1918 77%*

1919-1921 73%*

1922-1923 58%

1924 46%

1925-1929 25%

1930 -1931 25%

1932-1935 63%*

1936-1940 79% **

1941 81%**

1942-1943 88%

1944-1945 94%

1946 -1951 91%

1952-1953 92%

1954 -1963 91%

1964 77%

1965-1981 70%

1982-1986 50%

1987 38.9%

1988-1990 28.0%

1991-1992 31%

1993-2001 39.6%

2002 38.6%

2003-2012 35%

2013 38.6%

* The top rate in these years only applied to people making $1 million or more.

** The top rate in these years only applied to people making $5 million or more.

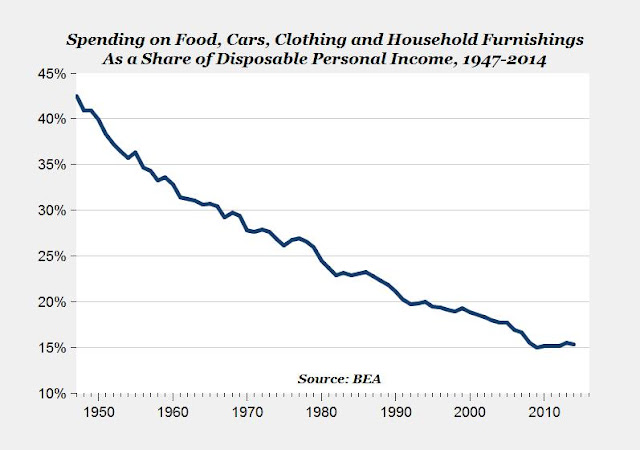

Fair enough, but it is important to remember that price depends not just on the ability to supply stuff (i.e., the technology and efficiency of the manufacturing sector) but also on demand for stuff in general. While all of us consume more stuff than our parents did, we consume many things that aren't physical stuff at all. The price of all my TVs pales in comparison to my accumulated payments to Direct TV, as does the price of my smartphone to the cost of the service contract that came with it. And don't get me started with what I spend on healthcare.

Fair enough, but it is important to remember that price depends not just on the ability to supply stuff (i.e., the technology and efficiency of the manufacturing sector) but also on demand for stuff in general. While all of us consume more stuff than our parents did, we consume many things that aren't physical stuff at all. The price of all my TVs pales in comparison to my accumulated payments to Direct TV, as does the price of my smartphone to the cost of the service contract that came with it. And don't get me started with what I spend on healthcare.